| CISLAC | Civil Society Legislative Advocacy Centre |

| DGSO | Domestic Gas Supply Obligations |

| DPR | Department of Petroleum Resources |

| ECA | Excess Crude Account |

| EFCC | Economic and Financial Crimes Commission |

| FAAC | Federal Account Allocation Committee |

| GMD | Group Managing Director |

| IOC | International Oil Company |

| NCC | Nigerian Communications Commission |

| NDDC | Niger Delta Development Commission |

| NEITI | Nigerian Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative |

| NERC | Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission |

| NGMP | Nigerian Gas Master Plan |

| NGO | Non Governmental Organisation |

| NNPC | Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation |

| NOC | National Oil Company |

| NPAM | Nigerian Petroleum Asset Management Company |

| NPDC | Nigerian Petroleum Development Company |

| NPRC | Nigerian Petroleum Regulatory Commission |

| NSIA | Nigeria Sovereign Investment Authority |

| OGIC | Oil and Gas Sector Reform Implementation |

| OML | Oil Mining Lease |

| OPA | Offshore Processing Agreements |

| OPL | Oil Prospecting Lease |

| OPTS | Oil Producers Trade Section |

| OSP | Official Selling Price |

| PIB | Petroleum Industry Bill |

| PINGIF | Petroleum Industry Governance and Institutional Framework |

| PPMC | Pipelines and Product Marketing Company |

| PPPRA | Petroleum Products and Pricing Regulatory Agency |

| PSC | Production Sharing Contract |

| RMAFC | Revenue Mobilisation Allocation and Fiscal Commission |

| RP | Realised Price |

| RPEA | Refined Products Exchange Agreements |

This report provides a concise analysis and assessment of three key areas of the

Nigerian petroleum sector: firstly the Petroleum Industry Bill (PIB) in the historical

context of the past 15 years, the political context of the last 12 months of the Buhari

administration and finally in terms of the current draft Petroleum Industry Governance

and Institutional Framework (PINGIF) bill which replaces the institutional aspects of

the PIB; secondly, the current quality of data concerning the petroleum sector

(specifically in terms of onshore vs. offshore oil) and thirdly events and outcomes of

significant recent legal activity in the sector.

This assessment is complemented by relevant transcriptions from interviews with

industry experts as well as a categorised bibliography. The report was developed

and drafted after a period of initial background reading (and reading of contemporary

news/analysis) followed by interviews with industry experts based on a semistructured questionnaire (see Appendix A) followed by updating relevant sections of

the report. For the interviews, to ensure consultations were not protracted, experts

were invited to focus on questions they were both most interested and best informed

to respond to.

This section investigates and analyses the PIB from an historical, political, financial

and regulatory perspective, assessing onshore vs. offshore aspects. The section

also plays devils advocate from a corporate, federal and state government, NGO and

investors perspective in terms of tax, geology and regulatory perspective. While the

PIB has now been broken up into separate pieces of legislation, beginning with the

institutionally-oriented Petroleum Industry Governance and Institutional Framework

(PINGIF) bill currently being discussed in the National Assembly, it is still worth

assessing the issues raised through the PIB process, as they are likely to re-appear

across the new legislative track.

Successive Nigerian government administrations have tried to reform the petroleum

sector, with limited success. For the past fifteen years, the reform has centred on

policy and legislation (rather than the institutional reform promised by the PINGIF

bill). The policy and legal reform process began with the formation of the Oil and Gas

Sector Reform Implementation Committee (OGIC) under President Obasanjo in 2000

under the Chairmanship of Dr. Rilwanu Lukman then serving as the Presidential

Adviser on Petroleum and Energy.

By 2004, the OGIC had developed a national oil and gas policy, which covered

upstream, midstream, downstream and also petrochemicals. The OGIC was

reconstituted under President Yar'Adua in 2007, and the first draft of the PIB was

prepared and circulated under his administration. In simple terms, this draft

legislation separated the national oil company (currently, the Nigerian National

Petroleum Corporation - NNPC) from the regulator, set new fiscal provisions and

addressed community issues. The Jonathan government continued with further

drafts of the PIB, and on one reading began to prepare the NNPC for

commercialisation as a standalone national oil company by setting up the so-called

"strategic alliances" between the Nigerian Petroleum Development Company (NPDC)

and local oil firms, to take over the onshore assets divested by Shell and other

International Oil Companies (IOCs). However, despite the president and his oil

minister being from the Niger Delta, the PIB was not passed during the Jonathan era.

The reform process could have gone otherwise. During the era of high oil prices, the

Production Sharing Contracts (PSCs) could have been renegotiated to increase

government take. The three the three "re-opener" conditions – of the price of oil

rising above $20 per barrel, mega discoveries of reserves above 500 million barrels

and more than ten years period since the signing of the contract all obtained.

Alternatively, the Yar-Adua and Jonathan governments could have focused on

restructuring the NNPC and institutional reform. Another option would have been to

agree a strategic policy framework and an over-arching "petroleum master plan" (as

happened in the energy sector). Instead, since 2007, the PIB itself became the

battleground for policy disputes, principally between the government, which wanted

to shore up discretionary power and government take, the IOCs through the local

trade body the Oil Producers Trade Section (OPTS) and to a lesser extent local

companies belonging to the Lagos Oil Club.

What are the most salient private sector issues that blocked the passage of the bill?

Referencing the consulting firm McKinsey's "Commentary on the Petroleum Industry Bill"

(produced in 2013 but not publicly available), which itself draws on and develops

the 2009 OPTS Memorandum on the PIB , we can note the following critical

comments:

It should be noted that local oil companies did not raise strong objections to the PIB,

presumably because they stand to benefit from the very discretionary processes that

remain in the draft legislation (or alternatively, that they had much to lose by

speaking out).

In terms of royalty rates and a fiscal regime, successive versions of the bill

introduced different frameworks. For instance, the 2011 iteration prescribed a

progressive royalty linked to production rates and oil prices with differentiations for oil

and gas. In contrast, the 2012 update (the most recently available draft), stated (in

clause 197) that, "There shall be paid in respect of licences, leases and permits

under this Act such royalties, fees and rentals as may be contained in this Act and in

any regulations made by the Minister pursuant to this Act." There was in other

words no explicit reference to specific royalty rates in the main fiscal provisions

clause, or elsewhere in the PIB. However the savings provisions indicate the

existing royalty rates will continue to apply pending new regulations by the Minister.

There was speculation at the time about the royalty regime that would subsequently

be proposed, along the lines that,

"Information from official sources suggests that the minister is considering a new royalty regime which would replace the existing single-tier royalty regime with a twotier regime, where the total royalty would be an aggregate of two distinct royalties: the royalty by average daily production plus the royalty by value based on price. Under the two-tier regime, production from all fields would attract royalties. The significant impact would be that producers from deep offshore fields which currently pay no royalties would become liable to pay royalties."

We can contextualise discussions around royalty rates in the PIB with a quick international comparison:

| Country | Royalty Rate |

|---|---|

| Argentina | 12% of wellhead value |

| Australia | Between 10-12.5%, depending on size of acreage |

| India | Onshore: 12.5%; shallow water: 10%; deepwater: 5% (for first 7 years of commercial production, 10% thereafter) |

| Kuwait | 15% |

| Mexico | If oil price is below US$48 per barrel, a royalty rate of 7.5% is applicable; when the price is equal to or higher than US$48 per barrel, the royalty rate is determined according to this formula: [(0.125 x Oil Contract Price) + 1.5]%. |

| Nigeria (current) | Onshore & shallow offshore: 20%; offshore up to 100m: 18.5%; offshore 100-200m: 16.67%; deep offshore, inland basin: 10%; 201 to 500m: 12%; 501 to 800m: 8%; 801 to 1000m: 4%; 1000m+: 0% |

| Saudi Arabia | Royalty rate stipulated in each petroleum concession agreement |

| US | 18.75% regardless of depth on federal offshore seabed (although there are some royalty-free leases in the Gulf of Mexico) |

| Venezuela | 30% (may be reduced to 20% if oil field is otherwise not economically exploitable) |

In terms of what a recommended royalty rate should be for Nigeria, the focus should

above all be on simplicity. Nigeria's fiscal regime, along with other aspects of

governance arrangements, are currently too complex and add yet another layer of

opacity to the sector. A flat royalty rate, say of 15% across all fields (in line with

Kuwait) can be recommended. Deep offshore (1000m+) attracted no royalty at a

time when these fields were unproven. While still far more expensive to produce oil

at this depth (in comparison to onshore and shallow offshore), the deep offshore

reserves are vast. The caveat for recommending a flat 15% rate is that it must be

placed in an overall fiscal context and present a globally competitive total

government take, especially given the negative connotations often associated with

the petroleum sector in Nigeria.

While formal engagement with private oil companies was weak during the Yar-Adua

and Jonathan years, lobbying and influence behind the scenes was at times been all

pervasive. Former Shell Nigeria chief Ann Pickard admitted in private to an

American Ambassador that "Shell had seconded people to all the relevant ministries

and that Shell consequently had access to everything that was being done in those

ministries."

This highlights a key political timeframe issue in Nigeria. Policy and legal reform in

such a mature and labyrinthine sector can hardly be completed within one four year

term of government, given the complexities, legacy issues and local and international

vested interests.

Despite Shell's longstanding history in Nigeria and at times close relationship with

federal government officials, as noted above, the company has been divesting its

onshore assets in the past few years as part of a strategic review process, which

began in 2010 in the face of mounting security risks and loses. The company has

suffered more than all others operating in Nigeria from pipeline vandalism, militant

attacks and oil theft, losing $1bn in 2013 alone due to sabotage. Shell sold eight

blocks for a total of $2.7bn in 2012. Shell's divestment was part of a trend. In the

same year, Conoco Phillips sold its stake in the Brass LNG project as well as other

upstream assets and a power plant to local company Oando for $1.79bn. In the past

five years, the IOCs switched their focus to more secure and operationally

straightforward deep offshore operations.

These divestments presented an opportunity for Nigerian oil firms to step in and

continue to develop the fields in the name of local content. Several local companies,

such as Oando, Sahara and Seplat (as well as older players such as Conoil) became

well established under Jonathan and poised for growth. However, revelations in

early 2014 by the former governor of the Central Bank, Sanusi Lamido Sanusi, that

there was a $20bn shortfall in oil revenues from the NNPC to the treasury through a

range of bad practices (such as a fixed domestic crude allocation, crude oil swaps,

revenue retention by the NNPC and so on) highlighted there had likely been massive

oil theft. This was on the back of the fuel subsidy crisis in 2012 (the federal

government attempted to remove the fuel subsidy without warning on January 1st of

that year, effectively more than doubling the price of fuel (from 65 naira a litre to at

least 141 naira). The subsequent massive street protested led to a period of panic in

government, which in turn led to a series of probe committees and reports to

examine suspected massive corruption in the subsidy scheme.

The focus on applying more discipline under Buhari, in the era of lower oil prices and a less forgiving (and generous) attitude by a northern President towards unrest in the Niger Delta, raises the question of whether the burgeoning Nigerian onshore local content success story of a few years ago may continue, and what prospects there are for onshore oil in Nigeria going forwards, beyond the existing joint venture operations. While onshore (and shallow offshore) oil remains technically the most cost effective option in Nigeria (in contrast to deep offshore, which at this stage in the market is an investment challenge, even given the high prospectivity of certain acreages), local companies bought their assets at the highest possible valuation; some are over-leveraged and facing financial difficulties. Certainly, the fate of the two more dubious NPDC strategic alliance partners - Atlantic Energy and a subsidiary of Seven Energy – looks doubtful, with Atlantic energy already put up for sale, and a preferred bidder identified. As one industry expert interviewed for this report noted,

"Local content became a byword for corruption, and the whole concept was totally abused. That should be combined with the fact that Buhari just cannot stand corrupt Nigerian businessmen. He feels more comfortable with foreigners. If he is doing anything with the private sector, just look at the oil lifting contracts. He's definitely veering more towards the IOCs and more towards the big international traders. From that point of view, you could argue that he is rolling back the local content that developed previously. Instinctively he would replace that local content with state institutions because of his aversion to a corrupt private sector. But, he is also mindful I think, but not mindful enough, that state institutions can also be hijacked for corrupt purposes."

However, Buhari's possible aversion to reinvigorating the local content story needs to be set against a possible reaction to his attempt at an uncompromising stance in the Niger Delta. The recent bombing of the underwater Forcados pipeline – itself showing signs of a sophisticated approach to sabotage – is a clear message from the Niger Delta that a former military general will not be able to use the top-down power of the state to enforce security and stability in the Niger Delta.

The choices facing the Buhari administration have been stark. Unlike the previous oil

price drop in 2009, there has been no fiscal buffer available to smooth out falling

revenues from the falling price shock (the Excess Crude Account – a fund to collect

oil revenues above the benchmark price set in the annual budget – had been

emptied under Jonathan). Many states in Nigeria were considered (by Sanusi

among others) to not be economically viable during high oil prices; so much more so

when their revenue allocations have been dramatically cut more recently. The

revenue-generating proposal to sell or incorporate some of the joint-venture assets

would face both philosophical resistance from a president who may regard those

assets as national patrimony, and economic resistance in terms of the potential

future accusation of selling assets at a low price (assuming the oil price rises in the

years to come).

Again, lower foreign exchange oil revenues to government have put the naira under

immense pressure; Buhari has staunchly refused to devalue, leading to a yawning

divergence between the official Central Bank naira exchange rate and the black

market rate. Meanwhile, foreign reserves have dropped to their lowest level in years,

presently around $27bn. Those who considered Nigeria to be a leading component

of the "Africa Rising" narrative have been dealt a harsh lesson in the fragility of the

non-oil economy (and the underlying linkages between the non-oil economy and

petroleum).

Above all, the policy and legislation approach of the past fifteen years of reformist

effort has ended in stalemate. Buhari, the former oil commissioner in the late 1970s,

appointed himself the Minister of Petroleum (as Obasanjo had done during his two

terms in office from 1999-2007) and appointed former Executive Vice Chairman of

ExxonMobil Africa Operations, Emmanuel Kachikwu, as his junior minister (Kachikwu

had previously been appointed group managing director (GMD) of the NNPC in

August 2015).

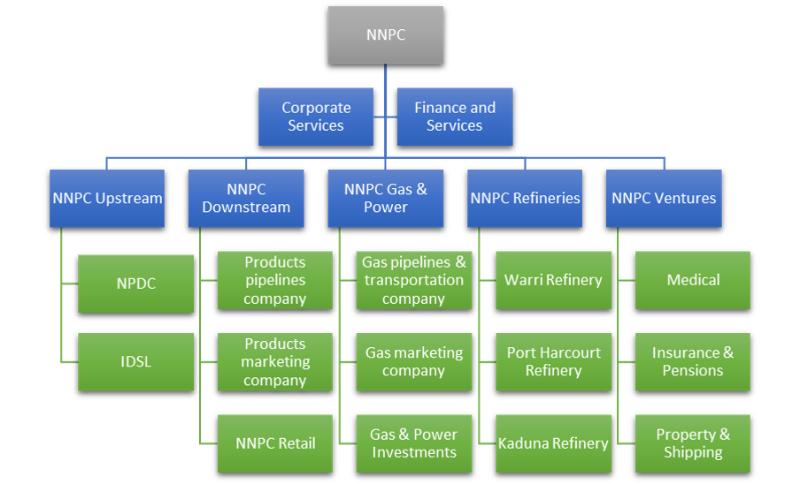

While President Buhari has made numerous remarks about revamping local refining

capacity (a favoured topic from his time as petroleum commissioner), Kachikwu has

focused so far on internal reform of the NNPC. In March 2016, he announced that

the NNPC has been restructured into seven coordinating units: an upstream unit, a

downstream unit, a refinery unit, a gas & power unit and one responsible for other

ventures. In addition, he outlined a group-wide corporate services unit, as well as a

finance and services company. Each new unit is responsible for existing NNPC

subsidiaries and each will be led by a chief executive officer.

What was noteworthy about Kachikwu's restructuring announcement in March was what he didn't say: he made no mention of the successor to the PIB, the PINGIF bill (drafted by the Nigerian Senate and about to be discussed in both the Senate and the National Assembly ). This prompts speculation about the extent to which the executive holds replacement legislation to be a priority (in contrast to the National Assembly), compared to more tangible issues such as the fuel shortage in Nigeria and revamping the refineries (through privatisation) to lesson the leverage of petroleum product importers. The most optimistic view is that the National Assembly and the executive are working in sync, based on an agenda set by the Senate but agreed to in general terms by the President. The PINGIF would therefore be the first in a series of up to five bills in total (the others addressing the fiscal regime, upstream, downstream and gas), that, given a closely sequenced or even simultaneous approach (with different bills presented to their specifically National Assembly committees) could even all be passed during this parliament. Observers suggest that the punitive hike in royalty rates that created resistance during the PIBera would likely not be repeated in the fiscally-focused bill, and suggest that the more strategic approach in evidence with the PINGIF may be repeated with a progressive royalty system linked to oil prices, in place of flat percentages.

However, this hope of a completed package of legislation may be idealistic, based

upon the prior performance of the National Assembly, but also on internal sabotage

factors (which may explain some uncertainty in Kachikwu's recent communication of

the restructuring of the NNPC). What will be interesting will be to track performance

and decision making in petroleum sector governance against APC policy objectives

(summarised in Appendix 2 of this report).

Already, informed industry watchers in Nigerian civil society have noted an absence

of enthusiasm for the more difficult task of industry restructuring based on legal

reform. As the executive director of well reputed Abuja-based NGO CISLAC, Auwal

Ibrahim Musa (known as Rafsanjani) has noted,

"CISLAC recalls that the Minister for State Petroleum Resources, Dr. Ibe Kachikwu, said that Nigeria is losing $15 billion (N3trillion) annually due to non-passage of the Petroleum Industry Bill (PIB) into law. We note that despite the restructuring going on the in the NNPC, the fundamental surgery that is required for the sector to be effective and accountable can only be found with the passage of this law which has been elusive for the past 12 years," Rafsanjani said.

It may be that both Buhari and Kachikwu are mindful that by 2018, the election

season will have started in earnest and are keen to avoid repeating the timeconsuming

errors of the PIB process by focusing on non-legal reform upstream and

downstream and more practical efficiencies (Kachikwu fired eight executive directors

of the NNPC when he became its boss). In that regard, they may become

increasingly at loggerheads with parliamentarians and civil society activists.

Nonetheless, the PINGIF is a relatively short (45 page) document which avoids the

problematic aspects of the PIB summarised above. A focused joint effort by the

National Assembly could agree on a uniform draft and submit to the President for

review. It is therefore worthwhile providing an initial if cursory assessment, with a

note of caution that the PINGIF may still go the way of the PIB.

The most notable components of the Petroleum Industry Governance and

Institutional Framework bill are:

While breaking the PIB up into its constituent parts, beginning with institutional

restructuring package that is light on detail appears to be learning a painful 15 year

lesson, the key contentious aspects of the PIB remain in store for future legislation

(and most likely a future administration). The key missing elements are:

Even the relatively modest aims of the PINGIF will not be guaranteed a smooth ride, either through the National Assembly (assuming the law can be passed and signed off by the President during this parliamentary term) or in terms of its subsequent implementation (likely to begin in earnest only after the 2019 elections). The new NNPC will still be one of Nigeria's largest companies and a source of patronage, which means there is likely to be strong internal resistance to change within the organisation. In addition, the more commercially-focused and autonomous national oil company will have to compete with more established IOCs (and the best of the local companies) to attract skilled workers – in short supply in (and from) Nigeria. Quite apart from these technical issues will be the legacy perception of a Nigerian national oil company (even after a rebrand), especially given more established national oil companies have suffered tarnished reputations in recent months. Finally, the new regulator will be in charge of the pricing of petroleum products (a sensitive issue, as the street protests of 2012 showed) and just like the electricity regulator NERC, become vulnerable to politicisation once again.

This section investigates and analyses existing data from the NNPC, Central Bank,

FIRS, and other data sources, focusing on availability of information and the most

significant leakages in the system, which occur through oil sales revenues. This

section identifies contradictions within and between data-sharing, accuracy and

integrity.

One of the junior minister Kachikwu's early achievements as Group Managing

Director of the NNPC (before being appointed junior minister) was the publication of

monthly performance data reports, which began in August 2015 (at the time of writing

this report, six have now been published, up to January 2016). All Annual

Statistical Bulletins since 1997 have also now been published. The NNPC also

announced, in its December monthly report, that it will produce an annual report in

the second quarter of 2016, which will provide information on NNPC's corporate

governance, operational activity and financial performance. This marks a new era of

transparency for the NNPC, after over a decade of non-reporting. As an NNPC

spokesman has said, "Before, nobody could even see what our books were like,

whether we were operating at a loss or . . . at a profit. It's a new NNPC. We want to

be as transparent as possible." The monthly reports follow a standardised format

and provide data on crude oil and gas production, domestic supply of crude, refinery

operations, petroleum products supply from Offshore Processing Agreements (and

monthly sales revenues), group financial performance, crude and gas sales revenue,

financial flows to the Federation Account and to the Federal Account Allocation

Committee (FAAC) – the body which allocates revenue to the states on the basis of

an agreed revenue sharing formula - as well as a closing sundry section on "Key

Determinants for Change".

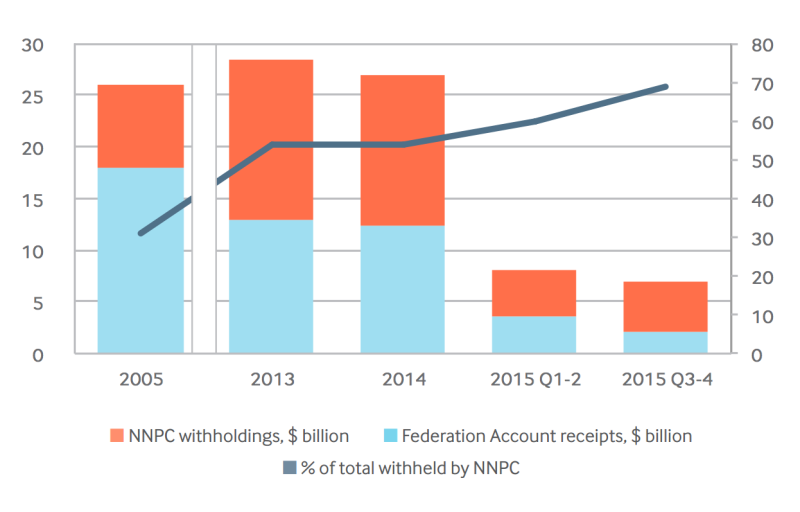

The December report shows the difficulties the NNPC has with its own accounts (the NNPC has previously been described as "unauditable" ). For instance, a table on the Naira proceeds from the sale of domestic crude oil & gas shows a total sales value of 1.67tn naira, with only 1.01tn available in receipts (i.e. over 600 billion naira unaccounted for). The overall financial performance of the NNPC in the December monthly report shows that the company ran at a loss of over 267 billion naira (up to November and unaudited). This reflects the lack of independent budget control the NNPC has over its finances, particularly in terms of crude oil sales. Sanusi's "missing $20bn" (which became a catchphrase on Nigerian social media) was further refined in March 2016 after Nigeria's auditor general submitted a report to the National Assembly stating that the NNPC had failed to remit $16bn in oil sales to the treasury for 2014 alone. According to section 162 of the Nigerian constitution, oil revenues must be remitted to the Federation Account (minus expenses), with operating costs covered by the annual national budget. However, successive GMDs have succumbed to political pressure to divert oil sales revenue for other purposes.

The following week, the Revenue Mobilisation Allocation and Fiscal Commission (RMAFC) joined in the attack, alleging that the NNPC has withheld $25bn from the treasury between 2011 and 2015. The divergence in figures between different bodies highlights the difficulty in tracking down how much revenue has leaked out of the NNPC. These leakages also do not account for the up to 250,000 barrels per day of Nigerian oil lost through criminal theft.

The most comprehensive report so far on crude oil sales to date has been the Natural Resource Governance Institute's (NRGI) August 2015 report, "NNPC Oil Sales: A Case for Reform in Nigeria". This report builds upon the PwC report published in February 2015 on unremitted oil sales proceeds (and the Memorandum to the Senate on non-remittance of oil revenues published by the former central bank governor , commissioned by the Ministry of Finance and published through its parastatal, the Office of the Auditor General. The NRGI report highlights five urgent problems associated with NNPC crude sales:

1. The Domestic Crude Allocation (DCA)

The DCA was originally intended to ensure that sufficient Nigerian crude was set

aside for local refining. 445,000 barrels per day are set aside for the NNPC to

sell to its Pipelines and Product Marketing Company (PPMC) subsidiary.

However, the country's refineries can only process up to 100,000 barrels per

day, which leaves over 300,000 barrels per day to re-route into oil-for-product

swaps (payments for which go into separate accounts which are then available

for NNPC officials to spend from freely). The NRGI report notes that for 2013,

the Federation Account only received 58% of the $16.8bn value of domestic

allocated crude. The report also notes that the amount retained by the NNPC

had risen dramatically in recent years, up from 27% retention in 2004. The report

recommends that the DCA fixed amount of domestic allocation be scrapped.

2. NNPC Revenue Retention

The NNPC has no established method for financing its operations (and regularly

is unable to fulfil its cash call obligations to the joint ventures with the IOCs). In

conflict with Section 162 of the constitution, Section 7 of the NNPC Act enables

the corporation to maintain a "fund" to cover its operational costs. The report

notes that the NNPC retained revenues from the sale of 110 millions of barrels of

oil from one block controlled by its subsidiary, the NPDC – worth $12.3bn alone.

Furthermore, the relationship between the NNPC's trading subsidiaries and its

JVs with Swiss commodity traders is also opaque and has been described as a

"financial black box." Again, proceeds from oil sales from the NPDC are not

remitted to the treasury – the PwC report estimates $6.82bn in total earnings

from this source in nineteen months between 2012 and 2013. The report

recommends resolving the conflict between the constitution and the NNPC Act by

providing clear rules on NNPC funding. As noted in the analysis above, the

PINGIF would provide the basis for doing so, but there would need to be more

detailed regulations on national oil company (and NPAM) funding to prevent a

falling back into the current political patronage framework.

3. Oil-for-product swap agreements

As noted above, surplus oil available from the PPMC via the DCA is available to

be swapped for refined petroleum products. Under Offshore Processing

Agreements (OPA), the contract holder is supposed to lift crude, refine it

overseas and import the refined product back to the NNPC. This is nominally a

good idea, given that the NNPC has lacked the cash to pay for imported fuel, but

has crude available. The report notes that between 2010 and 2014, over $35bn

of crude was sold in swap deals, with over 20% traded via poorly structured deals

with just two companies. The NRGI estimates that losses from three provisions

in a single contract could have resulted in losses of $381m in one year alone.

The report recommends that the OPAs are scrapped, with the alternative

mechanism of Refined Products Exchange Agreements (RPEA) used to deliver

better returns. Under the RPEA, a trader is allocated crude, against which they

are responsible for importing specified products worth the equivalent amount,

minus expenses.

4. The abundance of middlemen

The report notes a glaring problem with crude oil sales in Nigeria compared to

international benchmarks: the country relies on selling its crude via trading

companies, rather than directly to end-users (refineries overseas). "Nigeria is the

only major world oil producer (i.e., producing more than one million barrels per

day) not experiencing full-scale conflict that sells almost all of its crude to

middlemen, rather than end-users." These middlemen - who include politically

exposed persons (PEPs) - often have no technical or even financial capacity,

having been granted term contracts for political and patronage purposes. They

rely on Swiss commodity traders to deliver on the transactions. The report

recommends that term contracts be awarded through open, competitive tender

using performance-based criteria, developing robust due diligence procedures

that avoid payments to PEPs.

5. Corporate governance, oversight and transparency

This section of the NRGI report is now a little out of date, given that the NNPC

has now started producing monthly performance reports, has published its annual

bulletins and is planning to publish an annual report later this year. Its

recommendations on publishing data and commissioning regular external audits

of the NNPC are already being actioned. However, its section on empowering

accountability actors remains relevant:

The report also provides five important recommendations on addressing the NNPC's underlying problems.

In an update published at the time of finalising the report (March 31st), the NRGI published an update suggesting that the core leakages within the NNPC remain, as indicated by the following republished chart.

The most important and compendious source of data on the Nigerian oil sector in the

past eight years has been via the Nigerian Extractive Industries Transparency

Initiative (NEITI), the Nigerian implementation of the EITI. The most recent NEITI

report was for the 2012 financial year, although it was released in 2015. The 2012

report includes a 900-page appendix, which provides quite disaggregated information

on especially royalty and petroleum profit tax contributions, though as discussed

below the NEITI analysis is not without its own problems.

There is a general problem of under-assessment of royalty due in the case of PSC

entities in the NEITI reports. The royalty computation for all PSC entities is a mere

51% of the computation of NEITI; put differently, the under-assessment in 2012

totalled US$ 366.2 million.

The NEITI notes in this regard that the "lingering price dispute has resulted in

revenue loss of over US$ 4.04 billion in the last 7 years". This is of course a very

large (and quotable) amount; however, the phrase ‘revenue loss' would only be

applicable if indeed it turns out that the NEITI estimates are fully correct and

objective. This is unlikely. The reality is that disputes exist over both which oil prices

are applicable and which royalty rates are to be used, disputes which primarily

suggest poorly drafted regulations, scant in crucial detail.

The gargantuan appendix to the NEITI 2012 (in excess of 900 pages) gives some

sense of the nature and flavour of the dispute over the royalty computation which

marred many key deepwater offshore operations at the time of the NEITI report. To

give a sense of the issues, we summarise NEITI views and IOC comments thereon

for Shell, Esso and Star Deep (i.e. Agbami) itself, all 3 of which exhibited significant

divergence in royalty computations between NEITI and the IOCs.

Royalty Contributions

The reconcilers appointed by NEITI noted that Star Deep did not pay any royalty in

2012. In their view, the royalty amount due in 2012 was US$ 66.5 million. It is

important to contextualise this assertion, however, by noting what seems a general

problem of under-assessment of royalty due in the case of PSC entities.

The royalty computation for all PSC entities is a mere 51% of the computation of

NEITI; put differently, the under-assessment in 2012 totalled US$ 366.2 million. In

the case of Joint Ventures, by way of contrast, the operator computation is 98% of

the NEITI one. The NEITI notes in this regard that the "lingering price dispute has

resulted in revenue loss of over US$ 4.04 billion in the last 7 years". This is of course

a very large (and quotable) amount; however, the phrase ‘revenue loss' would only

be applicable if indeed it turns out that the NEITI estimates are fully correct and

objective. This is unlikely. The reality is that disputes exist over both which oil prices

are applicable and which royalty rates are to be used, disputes which primarily

suggest poorly drafted regulations, scant in crucial detail.

The voluminous appendix to the NEITI 2012 (over 900 pages) gives a sense of the

nature and flavour of the dispute over the royalty computation which marred many

key deepwater offshore operations at the time of the NEITI report. To give a sense

of the issues, we summarise NEITI views and IOC comments thereon for Shell, Esso

and Star Deep (i.e. Agbami) itself, all 3 of which exhibited significant divergence in

royalty computations between NEITI and the IOCs.

Shell

Shell operates the Bonga deepwater offshore field, the first large such Nigerian field.

There is a small difference (123 000 bbls) in production estimates by barrel between

Shell and DPR for Bonga for 2012.The main issue, however, is the computation of

the royalty due for these barrels, with the Shell computation being half that of the

NEITI (USD 69.4 million vs USD 128.6 million). NEITI notes that Shell used a 1%

royalty rate rather than the 1.75% ‘as stated by the DPR'. The response by Shell is

worth quoting in full:

The reason for the difference between the royalty rate applied by NAPIMs in the tax return filed on behalf of the contract area and the rate applied by the contractor, SNEPCO, in the tax computation is due to the fact that ongoing negotiations between DPR and SNEPCO are yet to be concluded regarding the compromise/mutually acceptable royalty rate that should be applied for purposes of royalty computation and payment. The necessity for a mutually agreeable compromise arose because by virtue of the Section 61, subsection 1a, vii, of the Petroleum Act, Laws of the Federation of Nigeria, the applicable rate defined under the law for production in water depths beyond 1,000 metres, is actually zero percent. Considering that on the average the Bonga PSC is at water depths in excess of 1,000m, it would be expected that no royalty is payable from the Bonga PSC. However due to the practical fact that by nature, the sea bed is not static as obtains onshore, both DPR and SNEPCO recognised that there would be areas within the Bonga PSC that may be more or less than 1,000m water depth. Accordingly discussions commenced between both parties to ascertain the compromise royalty that should be applied. Unfortunately this has not been concluded and has formed part of the issues currently under dispute between NNPC and SNEPCO.

It is noteworthy that Section 61, subsection 2a and 2b, of the Petroleum Act, also recognises and supports that in the event of a dispute or disagreement as to royalty due, the tax payer is permitted to apply the rate it believes in pending resolution of the issue.

Presumably the values used (1% and 1.75%) constitute SNEPCO and DPR's

preferred values in the ongoing dispute. The issue appears to emanate largely from

poor legislation and (presumably) an unclear actual oil contract. Be that as it may,

the labelling of the difference in royalty due cannot simply be defined as ‘lost

revenue' in the manner done by NEITI.

Esso

Esso is the operator for the deep water field Erha, which first streamed oil in 2006

and which lies at a depth of around 1000 meters. There is (as with Shell) no dispute

between Esso and DPR (the regulator) over oil production in 2012, which both

parties agree was 45.7 million barrels. The royalty payable, however, is sizeably

contested, with Esso computing USD 8.2 million and the NEITI auditors USD 52.1

million. The NEITI uses the rate of 1%, referring to it as the ‘DPR Royalty Rate'.

Again, presumably this is the rate the DPR is aiming for in negotiations, but does not

appear to be a rate with a legislative mandate behind it.

It seems that the absence of clear provisions for dealing with different field depths

generates different approaches, often quite disparate. Thus, Esso distinguishes

between Erha Main and Erha North: the former's depth exceeds 1000 meters and

thus, Esso argues, no royalty is due, which would seem to be correct; in the case of

Erha North, however, Esso mysteriously applies a rate of 0.331%, which it says is

based on "exact measurement of water depth in the area covered". This does not

seem correct either: if Erha North is mainly or entirely shallower than 1000 meters

then the rate should simply be the applicable percentage as per legislation.

However, even here in the phrasing ‘mainly or entirely' one sees scope for

disagreement, pointing again to the issue of a lack of clarity in the PSC legislation. It

seems less an issue of dispute over water depth and more an issue pertaining to

how the royalty is to be computed given variable depths of a field; the NEITI main

report contains the following recommendations in this regard:

"The Ministry of Petroleum Resources should appoint an independent consultant who would confirm the accurate water depth level for these blocks and advise on an appropriate rate which should be agreed with the operators of the blocks…Alternatively, an amendment to the deep offshore and inland basin Act can be effected by the National Assembly to cater for the water depths in disputes."

In the case of Esso, and indeed most of the IOCs, a second contended issue leading

to valuation differences concerns which oil price is to be deemed the applicable one

for royalty and profit determination purposes, and specifically whether the Official

Selling Price (OSP) or the Realised Price (RP) should be used; invariably, the IOCs

use the realised price (that is the actual selling price) whilst NEITI uses the OSP, in

essence an advance pricing agreement. A number of IOCs in the appendix

discussions note that this is another issue currently under litigation.

However, the relevant provisions for PSCs in the Offshore Decree seem clear

enough, in preference of the realised price: "(1) The realisable price as defined in the

production sharing contract established by the Corporation or the holder in

accordance with the provisions of the production sharing contract, shall be used to

determine the amount payable on royalty and petroleum profit tax in respect of crude

oil produced and lifted pursuant to the production sharing contract." The NEITI

approach, on the other hand, is explained by them as follows: "The PPT Fiscal Value

(i.e. Volume and Fiscal Price and volume set out in the company's export template)

was reconciled with Audit reconciled volume and also with DPR and terminal

balances volumes. Fiscal value is to be determined on the basis of the higher of

Official Selling Price (OSP) and Sales Proceeds. The OSP is a crude oil pricing

method, which utilises average daily price of Dated Brent Spot. We applied the OSP

premium and discount spread to the dated Brent values supplied by NNPC to derive

the OSP."

It may well be that applying the higher value of a futures price and a realised price is

a preferable pricing method for royalties; certainly it would be preferable for the state,

since it would get the higher of two royalty computations. However, this is hardly the

issue. What is of concern is that basic policy parameters governing deepwater

offshore, such as pricing methods, are currently contentious in Nigeria.

Turning finally to the Agbami field, and Star Deep as the operator, the same issues

prevail according to the NEITI report: again there is no difference in estimates of

barrels produced between the operator and the DPR, at 85 million. The dispute,

however, arises from the fact that Star Deep did not pay any royalty, whilst the NEITI

auditors argue that a 1% rate is applicable. Star Deep is the only deep water

operator who paid no royalty, though this in all probability reflects the depths of

Agbami, where not only the average depth but (presumably) all well depths are in

excess of 1000 meters deep.

It is hard not to escape the conclusion that the efforts by the DPR to apply some form

of royalty where, narrowly-legally speaking it would not seem to apply, are a belated

effort to secure more gain from the deepwater offshore fields, given increased

awareness of their lucrativeness. This is of course understandable, but it is not clear

where the rates attributed to the DPR come from, or what their legal status might be.

This reflects the weak institutional role of the DPR, as a non-autonomous regulator

historically dependent on the NNPC for its revenues, and on oil company helicopters

for access to facilities.

In terms of repercussions of wrong calculation of water depth i.e. if it is found that the

oil companies had wrongly calculated the water depth over a period, it is likely that at

least under the current administration, a penalty would be imposed which is

calculated on the basis of owed revenue, rather than any other form of punitive

requirement. This would reflect higher levels of administrative competence found in

government institutions focused on extractives in general. For instance, apart from

the NNPC restructuring, after a period of neglect under Jonathan, NEITI looks set to

receive a new lease of life. The mining minister, Kayode Fayemi, has been

appointed Chair of the NEITI board – the National Stakeholders Working Group

(NSWG). Fayemi is an accomplished technocrat, well respected in the donor

community and already with a good command of his mining brief. Meanwhile, Waziri

Adio, the former Communications Director of NEITI during the Yar'Adua years, has

been appointed Executive Secretary. Adio is also a well regarded technocrat.

Beyond the work of NEITI, there are two structural issues that currently prevent its

work from being as comprehensive as it might be. First, the PSCs and JV contracts

are not publicly available, so it is not possible to assess what should be paid against

what was paid. Its also not possible to scrutinise other contractual issues such as

tax holidays and waivers and whether RP or OSP is used as the royalty base.

Second, there is no data available to NEITI on production volumes from the wellhead

or from flow stations (despite IOCs sharing pipeline infrastructure and a system of

fiscal meters at all Custody Transfer Points). While the new NNPC monthly reports

provide production data on NPDC run Oil Mining Leases (OML), the reports do not

currently include production data for all OMLs.

This brief section assesses aspects of the prosecutional processes and legal investigations in the Nigerian petroleum sector. Recent high profile scandals have implicated the highest levels of government in bribery. In 2009, Halliburton and its subsidiary Kellogg Brown and Root were fined $579m by the US government for enticing Nigerian officials to win a gas plant construction contract. An official investigation in Nigeria revealed that President Obasanjo might have been a bribe recipient. Meanwhile, Shell and ENI paid over $1bn to the Nigerian government for an oil block in 2011; a payment which was effectively then transferred to the military dictator General Abacha's former oil minister. This case is ongoing in the Italian courts, with President Buhari also ordering that the case be reopened in Nigeria. As two major IOCs are involved and there is the hypothetical spectre of a lucrative Oil Prospecting Licence (OPL) being withdrawn, OPL245 is easily the most significant live legal case in the Nigerian petroleum sector today.

In terms of a brief background to the case, in 2011, the Nigerian subsidiaries of

Royal Dutch Shell and the Italian IOC ENI agreed to pay US$1.092 billion for

OPL245, one of Nigeria's most potentially lucrative oil blocks (speculated to contain

up to nine billion barrels of oil). While the payment was made to the Nigerian

government, the same amount was transferred to Malabu Oil and Gas, which is

linked to former oil minister and convicted money-laundered Chief Dan Etete. While

oil minister (under General Abacha), Etete had granted the block to Malaba.

Shell and Eni both deny paying Malabu for OPL245 – a claim which is backed up by

the superficial fact that they transferred their payment to the Nigerian government.

However, the prosecution asserts that in reality, both companies were well aware

that the deal would benefit Malabu (with evidence of face-to-face meetings between

the two companies and Etete). Commentators agree that it is unlikely that the Global

Witness dream scenario – of the prospecting licence being removed from Shell and

Eni's ownership – will transpire. They point to one of two more feasible scenarios.

Either the case will rumble on for years in the Italian courts, or Shell and Eni may

admit some degree of culpability and negotiate with the Nigerian government. This

would be in keeping with the current phase of Buhari's stance towards past

misdeeds. As one industry observer noted,

"There's been the usual round of arrests and investigations, but the proof is in the pudding in terms of whether they prosecute and actually find people innocent or guilty and the issue of punishment. At the moment, what we've got is the situation where Buhari is still trying to get money back, so some people he is treating with kid gloves, like [Aiteo boss] Benny Peters (and Sahara too), trying to get them to deliver cargoes under old swap agreements, so that he can get money that's owed back first. The question is, what does he do with these people afterwards? As far as I know, Sahara have been rehabilitated, because he hasn't really had much of a chance to hold them to account because they are Nigeria's largest indigenous oil trading company. What he [Buhari] can do is very limited by various things like needing to get the money back, obvious political pressures, and I'm still detecting elements of corruption going on; I'm not sure whether its Buhari being pragmatic or whether its other people underneath him freelancing."

While there is evidence of a joined-up and collaborative approach between the US and UK crime agencies and the EFCC towards the more obvious sins of the DiezaniJonathan era (most notably, investigating the former Minister of Petroleum and her associates participating in the Strategic Alliance Agreements), the question is whether Nigeria will be able to convert investigations and prosecutional processes into convictions. In the past, malfeasance in politics and petroleum in Nigeria has only been successfully prosecuted by outsourcing justice to other jurisdictions (alongside the Halliburton case mentioned above, the conviction of Etete in France, and former Delta State governor James Ibori in the UK are the two other notable case studies). This highlights a key point about prosecutional processes in Nigeria: they rely on strong institutions to succeed, and most significantly, they rely on a strong judiciary. This is precisely where Nigeria is weak. As one interviewee noted,

"In terms of legal cases, regarding the strategic alliance agreements, the EFCC has had a bit of a scattergun approach – I'm not sure what will happen. If they were to decide to prosecute, they might have a reasonably good case. The one thing I would say is that yes, there is a disciplinary stance, but of course with Buhari now there is a lot of pressure for the institutions – the EFCC and so on – to be more effective, but without institutional reforms I think there will be a limit to how much impact it is going to have in the medium and long term. The key point will also be the judiciary and how the VP [Osinbajo] will be able to push any of his planned reforms. Even for the EFCC that has been one of the issues – they can prosecute but then there is the judiciary and corruption in the courts."

The following verbatim transcripts (with minor editing for the purposes of readability) capture key points made during a series of interviews with experts on the Nigerian oil sector. The letter indicates their first name. While there have been citations from these transcripts in the above analysis, the fuller-length texts are presented below to provide more context to the expert's thoughts and opinions.

A a senior staff member (with a Cambridge PhD on Nigerian oil) at an

international think tank, which focuses on natural resource governance.

Less has happened that I would expect, even though Kachikwu does seem to be empowered to a degree. He hasn't actually achieved that much. I would have expected more financing deals to have been announced. However, what he is doing is quite good in that he is trying to fix the NNPC within the existing system and doesn't seem to be paying time and attention to the legislative agenda. The NNPC Act is 30,000 feet: there's so much you can do within it. That said, they haven't got all that much done in terms of restructuring: the problems that led to the missing $20bn scenario are still 100% in place and haven't been addressed. The company is putting out way more information, which I of course approve. The legislation doesn't seem to have the backing of Kachikwu or the President – not that they are against it, it's just that I don't think it will move through the National Assembly unless its an executive priority and it doesn't seem to be right now. I don't think it's a deliberate distraction, its just President Buhari has a small bandwidth in terms of what he can focus on and things he is not focusing on aren't really moving. I'm scarred by having followed the PIB for the last ten years, it's going to have really get off the ground before I pay any attention to it.

One interesting thing is whether the indigenous companies that grew so much under [former Oil Minister] Diezani can survive. They are highly leveraged and indebted they are earning less than they thought they would, but some of them were pretty promising and had really gotten off the ground. It sounds like they've been abandoned by this government.

A a Lagos-based oil and gas lawyer with deep familiarity with the PIB and PINGIF

The PINGIF is the initiative of the National Assembly. They put it together, they funded it, got consultants to work on it and they have come up with the product. As far as I know, there was input from the executive – they sat around the table and discussed various elements of the bill etc. Part of the reason the bill was delayed from December is because of the engagement with the executive. But it is not their bill and therefore – not because they don't think the content is good – they are not talking about the bill as much as they would be if this was something they had initiated and put to bed. I expect that if they do publish it as they have indicated that they will do, they will also take a very aggressive position in passing the bill. First and second reading will come in very quick succession. The public hearing is then another matter. The bill is unlikely to be particularly controversial. The principles are very simple, it's really dealing with government institutions and their role in the oil and gas sector. If it is controversial at all, it is to two sets of people: 1) the labour movement – their concerns around whether they are going to lose jobs or not. I know there were some mergers of government institutions involved – the DPR being merged with the PPPRA – what's it going to mean for them? 2) You potentially have concerns from the executive side – I'm going to put the ministry and the NNPC together – in the sense of whether they are losing power. However, the document has had good reviews people like Revenue Watch. I suspect that civil society will come out in favour of the document. It's going to be really hard for the executive to not implement the bill if it is passed.

In terms of whether the recent restructuring works with what is proposed in the PINGIF – I think it still does. From what I can see, what they have done is an internal restructuring of the NNPC which doesn't deal with some of the broader issues – so regulatory reform can't be dealt with outside of legislation. There is some unbundling of the NNPC that can't be done without legislation – you can't really break up the company without legislation. The PINGIF will do that. His restructuring will still hold from what I can see.

What they are planning to do is to have between three and five bills – the PINGIF bill which deals with administrative aspects, a bill that deals with the fiscal aspects, and then other elements that deal with upstream administration, downstream administration and gas administration. That I think is the policy position. What we've found is with the PIB being one bulk document you have a situation where you have different stakeholders who have different problems with small elements of the PIB, and that has held the PIB back. The PINGIF is the first bill, but a number of other documents will come subsequently. Hopefully we can achieve a situation where if there is a problem on the fiscal side – for example – its not going to delay the passage of the upstream or downstream administration bill.

The plan is to pass all the legislation within this legislative period. That's the risk that you face when doing it like this. The reforms have been on going since 2007, and something has got to be done. The executive and the legislature are agreed on this approach – let's try to break it up and deal with these issues one by one instead of in one document. From the legislative side, this is how I think it will work. The PINGIF bill will be dealt with by all the relevant committees – upstream and downstream – because the institutions being created cover both upstream and downstream. If separated properly, the fiscal bill will be dealt with potentially just by the upstream and finance committees of the Senate and the House of Representatives. Similarly, Upstream Administration will only be dealt with by the two Upstream Committees. Downstream will be dealt with by the Downstream Committees, and gas will be dealt with by the Gas Committee. If we follow that philosophy, we can push it within the calendar. The sensible thing to do – and I'm not sure whether they are doing this – is to work on this simultaneously. Don't wait for one to be passed to do the other. However, the foundation is this institutional reform [through PINGIF], because if you don't have that, everything else can't stack up.

There's a bill in front of the House of Representations seeking to increase royalty rates. That will be interesting because this is not necessarily supported by the executive, not because they don't think it should be higher, but because they haven't had time to consider what their policy position is. My instinct is that there will some increase at some point because there is now a populist dimension, with some civil society members accusing the government of colluding with the IOCs because they didn't raise royalty rates when they were supposed to. However, the level of increase may not be what people expect and whether that increase will be tied to some kind of oil price framework might be another thing.

The question is whether the increase will apply to everybody, or just to newcomers. From what we hear, people are less focused on the newcomers and more focused on catching out the guys that have been there before, and saying that from now, your royalty rates are going to go up. There's also a natural window in which it can be done – some of the assets will go up for renewal – a natural window for the companies already operating. For newcomers, the proof will be if you do a bid round and you see the kind of people you want are not interested, clearly your royalty rates don't work and you need to go back to the drawing board.

T a PhD student from the Niger Delta, writing a thesis on oil and the Niger Delta for a European university

The problem is the nature of the discussions around the PIB – with the issue of the distribution of revenues it was highly politicised and there were quite a number of interests, even within the Niger Delta, about what people want and questions like "what is a community?" and "what is a host community?" With the so-called host community fund, there is the question of who administers it. There was no consensus around these specific provisions for communities. Even when we had the PIB – before we move forward to the new suggestions, when we had the PIB discussions they were just discussions. One will say that there was no clear governance framework for these provisions in the Delta. In discussions with the author of the first draft of the PIB, he told me the idea was to have a community sovereign wealth fund, but still there was no answer to the question of whether this would be independent of the state governors and the community elites.

The new proposed legislation is based on avoiding the political issues. They don't want to go into contested areas. I'm not sure the government is prepared to confront the communities and regional interests, or the issues with the IOCs themselves – if the government is able to renegotiate the contracts and how they will manage the ownership of oil blocks – those powerful interests that control the oil industry in Nigeria. Politics is the Achilles heel of the Nigeria oil industry. The government wants reform without addressing the issues and I don't know how much will change if they go about separating out contentious issues, especially the onshore activities and who has what rights around the resources.

Security wise, operational-wise and even investment wise I would rather focus on offshore oil than onshore. It's more difficult for people to access – for instance Bonga is about 140 nautical miles from the coast of Bayelsa. However, there is some offshore oil that is closer to the communities, which people can easily visit. With the Amnesty Programme and the recent investments in security those facilities are quite protected. So strategically yes, offshore is a good plan. However, there is still so much oil onshore, and if communities have the perception that these facilities are being abandoned or being decommissioned, it might even increase local agitations to allow state governments to explore this oil within their own means and with their own partners. However, if you protect the Federal Government and the oil companies by moving away from onshore oil, but will the Federal Government willingly handover onshore blocks to state government (given that the legal framework states that oil belongs to the state)? This was one of the key issues that governed Shell's divestment of its onshore blocks. In Bayelsa, the local elites in Brass organised the youths to ensure that the onshore blocks around their communities are sold to local elites. Where they were sold to non-Bayelsans, they will attack and ensure that those people are unable to operate.

From my discussions and observations in the region I think two things are going to happen in the Niger Delta. Firstly they will change their strategy; there will be an increased narrative of human rights violations – just like we had in the 1990s. There will be attempts by local elites, local interests and local actors to push this human rights agenda – and even some from the international community. Secondly, you'll see that some people will try to sabotage the industry to demonstrate the lack of capacity of the state to protect oil industry infrastructure. You saw this in Delta State, where despite the military presence there was an attack on the oil industry requiring a certain level of technical expertise. So, there will be complementary strategies; some will engage in the human rights narrative around Buhari's new approach, while some others will demonstrate that the state cannot really protect the oil industry.

As an example, when the security contract [with Tompolo] was terminated, some exmilitant leaders told me that because they support the APC, the security contract would be transferred to them, not necessarily in its entirety. Recognising that this was not going to happen, they started to sabotage the industry. You should look at the press statements immediately after the attack; some ex-militant leaders pointed to Tompolo, saying he was behind the attack. What they were trying to do with that was to demonstrate to the President that we can protect this industry if you give us the job. However, there will not in my opinion be a return to the Niger Delta militancy of old because ex-militants are now too invested in politics, in properties and in different businesses in the region and beyond. They will no go full scale back into that kind of activity. There will not be large-scale insurgency with people living in the creeks in camps and all that, no.

C an oil sector journalist who focuses on Nigerian petroleum sector and is also co-author of various well-regarded analytical reports

There's been the usual round of arrests and investigations, but the proof is in the pudding in terms of whether they prosecute and actually find people innocent or guilty and the issue of punishment. At the moment, what we've got is the situation where Buhari is still trying to get money back, so some people he is treating with kid gloves, like [Aiteo boss] Benny Peters (and Sahara too), trying to get them to deliver cargoes under old swap agreements, so that he can get money that's owed back first. The question is, what does he do with these people afterwards? As far as I know, Sahara have been rehabilitated, because he hasn't really had much of a chance to hold them to account because they are Nigeria's largest indigenous oil trading company. What he [Buhari] can do is very limited by various things like needing to get the money back, obvious political pressures, and I'm still detecting elements of corruption going on; I'm not sure whether its Buhari being pragmatic or whether its other people underneath him freelancing.

Local content became a byword for corruption, and the whole concept was totally abused. That should be combined with the fact that Buhari just cannot stand corrupt Nigerian businessmen. He feels more comfortable with foreigners. If he is doing anything with the private sector, just look at the oil lifting contracts. He's definitely veering more towards the IOCs and more towards the big international traders. From that point of view, you could argue that he is rolling back the local content that developed previously. Instinctively he would replace that local content with state institutions because of his aversion to a corrupt private sector. But, he is also mindful I think, but not mindful enough, that state institutions can also be hijacked for corrupt purposes.

What is lacking with the PINGIF is that it say little about the processes, such as oil sales – a significant omission given the importance of funding and the black holes that have already resulted from NNPC's handling of discretionary funds. It was vague. It also gives Nigeria's oil minister to direct the new company's board on transfers of assets and other matters.

There is a case for saying that the 1993 PSC royalties were incredibly generous and those were designed at a time when there was no deepwater infrastructure. It was designed to get the deepwater to take off. Not all of that deepwater is developed and the companies are not now going into unknown territory, there is a lot of proven reserves there. There is therefore a case for hiking the royalties, the question is by how much. In theory you could argue that the royalties should be linked to the price of oil in a way that when the price goes up, the state's take increases, rather than just slapping higher royalties for the sake of it. Or, giving the companies a non-deserved free-ride. You just adjust it to whatever the oil price is. Of course the oil prices are low now, but then they were also very low when the deals were negotiated – I think they were about $10 a barrel. It is important to develop the deepwater – there's an awful lot of reserves there that have already been discovered and nobody's developing.

T works for an IOC (with interests in Nigeria) and has spent several years formerly providing analysis on the Nigerian oil sector

In terms of oil and gas governance, the impact of Buhari takes place on different levels; you have the immediate Buhari effect, so you had a bit of a change of tone at the top. The NNPC is a bit more of its own animal, but it cuts across the economy and had a bit of an impact. Apart from that, Kachikwu was quite a positive appointment. I understand – although it is just rumour – that even within the ministry there were some mixed views. I think compared to former oil ministers he's been a very positive appointment.

However, when you look at the process, the introduction of PINGIF separate from the PIB is a good move, but my concern in terms of managing the process is that when you look at Kachikwu's communication around NNPC reform, its been very poor. First NNPC issued a statement saying that they would break up the company into 30 different entities or companies that would be independent. The next week, you had seven operating entities. Shortly after that, when the unions pushed back, Kachikwu said that there wasn't actually any unbundling taking place. It's been quite messy.

As far as I understand what Kachikwu is trying to do, you have the longer term and the medium term aims – reforming the NNPC and breaking it up in accordance with PINGIF, but then you have the shorter-term issues where Kachikwu is trying to assert control trying to get a momentum towards greater accountability, but I'm sure its been that well managed. I saw an NNPC press release that was once again from one of the Yahoo email addresses, coming out late in the day. My suspicion was that there might have been an element of internal sabotage in play.

You are also seeing calls for him to be sacked and I think that's the thing about his relationship between Kachikwu and Buhari – it hasn't been completely clear to me either whether Kachikwu really has Buhari's ear on some of the core issues. I think that has played out in terms of discussion around the crude oil sales and the swap contracts and how best to do it. Again, it's a broader issue, because you might have pretty good advisers but are you willing to listen to them? Or, if you have a very set idea about what the plan is and you don't communicate it, that makes it even more difficult.

In terms of the fiscal terms, I'm not sure right now is the best time to do that. Because when you look at the investment environment for oil and gas in general, of course you have some challenges in that on the one hand you have onshore oil in Nigeria, which is in terms of technical cost not that expensive to extract, but then you have the offshore and then deep offshore which is quite expensive in terms of the baseline. You have basically two different cost environments – a low-medium cost environment and then a high cost environment. Anything that requires investment in a high cost environment at the moment is relatively difficult of course across the IOCs globally. A tightening of fiscal terms as seen in the PIB might be a bit problematic. What I don't know is what the government is thinking about this, because on the one hand you do have people who are relatively sophisticated and understand the market very well – I would suppose that Kachikwu would be in that category; on the other hand you have issues around Nigeria needing more revenue in the short term. The unclear factor to me is what Buhari's stance is.

In terms of legal cases, regarding the strategic alliance agreements, the EFCC has had a bit of a scattergun approach – I'm not sure what will happen. If they were to decide to prosecute, they might have a reasonably good case. The one thing I would say is that yes, there is a disciplinary stance, but of course with Buhari now there is a lot of pressure for the institutions – the EFCC and so on – to be more effective, but without institutional reforms I think there will be a limit to how much impact it is going to have in the medium and long term. The key point will also be the judiciary and how the VP [Osinbajo] will be able to push any of his planned reforms. Even for the EFCC that has been one of the issues – they can prosecute but then there is the judiciary and corruption in the courts.

This section provides a list of key reports, data and court cases that are relevant to the Nigerian oil sector, divided into four categories: legal, political, regulatory and historical.

APC Commitment (as stated in Manifesto and 100 Day Covenant)

Summary of Policy Dialogue Recommendations (May 2015)

First 100 days (quick wins and immediate actions)

Mid-term (3 to 18 months)

Long-term (18 months +)