Preliminary findings show there are a number of factors that come into play when pricing deepwater crude oil

in Nigeria and Angola. Most importantly, the pricing system is principally influenced by the market price of

oil (supply and demand) and oil futures (hedging and speculation).

Other key factors that drive the pricing of deepwater crude oil are evidenced in the terms and conditions of the

Production Sharing Contracts (“PSCs”) which relate to the division of the oil production between the

international oil company (“IOC”) and the national oil company (“NOC”). The latter is largely discussed to

discern specific contractual arrangements between the parties.

Key persons from the oil, financial legal and government sectors have been contacted with regard to the below

stated mandate. Persons contacted in the Nigerian and Angola governmental sectors have failed to respond

despite numerous attempts to contact them. HUMINT includes contact with individuals from the financial,

legal and non-governmental sectors. The majority of what was discussed with them has been collaborated by

public sources and is reflected in this paper.

The mandate is as follows:

Global oil prices have significantly dropped since 2014, heavily impacting the upstream sector in West Africa.

Given that the pricing of oil in the offshore/deep water industry is greatly influenced by the market and oil

futures, a key strategy for crude oil-producing countries is to decrease oil production (supply) to increase the

market price of oil. Diverging interests in OPEC, in particular, Saudi Arabia and Iran, as well as the shale

producers in the U.S. market, however, have resulted in steady production; as a result crude oil is heavily

flooding the market. A recent attempt by the top oil producers on 17 April 2016 to negotiate a freeze on

production and install a floor on crude oil prices was concluded without an agreement.1

Upstream (offshore/deepwater) production costs by nature are fixed, high and typically amount to the

expenditure of billions of US dollars per year.2 These production costs are factored in when calculating the

break-even price (“B/E price) of crude oil per barrel. Stated simply, profitability or loss is determined by the

B/E price because it measures at which point the IOCs and the NOCs begin to make a profit or loss. In upstream

projects, the production costs will be much higher than that of on-shore projects because of the risk, cost and

expenditure associated with offshore/deepwater exploration and production (“E&P”). OPEC, of which Nigeria

and Angola are members, has set the B/E price for crude oil at 52 US dollars per barrel (which is substantially

tempered because of Saudi Arabia’s low cost of production),3 and this far exceeds the current market price.

Considering this, a number of upstream projects have or will be deferred or permanently terminated to offset

losses.

It has been reported that since 2014, a total of 68 major upstream projects have been deferred to 2017. This

deferral amounts to approximately 170 billion US dollars in potential investment. Countries that require heavy

upfront investment (Angola, Nigeria and the Gulf of Mexico) account for more than 50 per cent of that deferred

production.4

Nigeria and Angola are the two biggest producers in Africa. Nigeria produces 1.6 million barrels per day5 of

crude oil that is low in sulfur and light and sweet,6 while Angola produces 1.72 million barrels per day7 of

crude oil that is also low in sulfur but heavy and sweet.8 The differing types of crude oil affect the marketability

and overall demand of the respective crude oils.9

Even though Angola’s crude oil is considered an overall poorer quality than that of Nigeria’s, it has higher

demand because its client base consists of rapidly growing countries. Nigeria relies mostly on European

countries’ consumption.10

Nigeria fluctuates between being the largest and second largest producer of oil in Africa.11 As oil accounts for

70 per cent of the Nigerian economy, the recent decline in oil price is severely impacting the country.

Approximately 70-75 per cent of Nigeria’s oil production is obtained via offshore drilling.12 “Deep-Offshore”

in Nigeria means any water depth beyond 200 meters.13

Recent years have shown number of IOCs sought out offshore areas in Nigeria to counteract the onshore risks

associated with the Nigerian oil industry. Due to the sharp fall in the price of oil, a number offshore projects

have recently been deferred or terminated.14 There are a number of deepwater projects that have yet to reach a

final decision for investment such as Bonga Southwest and Aparo (Shell); Zabazaba-Etan (Eni); Bosi, Satellite

Field Development Phase 2 and Uge (ExxonMobil); and Nsiko (Chevron).”15

Since the mid-1990s, the Nigerian government has entered into deep water E&P contracts with the IOCs on

terms that are estimated to be depriving the Nigerian government of 15 billion US dollars in oil revenue per

year.16 The Nigerian government however, did have the foresight to include a fifteen (15) year renegotiation

clause in these contracts, and is now in the process of renegotiating these terms. The form of these contracts

have changed with Production Sharing Contracts (“PSCs”) becoming the preferred agreement for the upstream

E&P sector. Considering the Nigerian NOC, the Nigerian National Petroleum Company (“NNPC”), has not

advanced with regard to its own commercial or operational infrastructure,17 Nigeria will continue to rely upon

IOCs for the foreseeable future.

Since 2010, NNPC has also entered into crude oil-for-product-swaps with traders which was received with

public discord.18 Countries usually engage in these swaps when they have nowhere else to turn. In this case,

Nigeria engaged in these swamps to prop up its ongoing fuel crisis:19 NNPC allocates a cargo of crude which

then goes through traders as middleman, and in return gets paid in gasoline and kerosene for the crude oil.20

These crude oil-for-product-swaps are conducted through “Offshore Processing Agreements (OPAs”) and

amount to 35 billion US dollars for the period 2010-2014. The OPAs are distributed through subsidiaries of

NNPC (such as PPMC)21 and are expected to be replaced by the Direct-Sale-Direct Purchase Agreement

(“DSDPA”) which will eliminate the traders as middlemen.

The Nigerian people are restless and discontent with the current state of the economy, and are urging for the

transparency and accountability of the NNPC. Following calls for transparency, NNPC started publishing

monthly Oil & Gas Reports in August 2015 for the first time in a decade. These reports outline inter alia the

upstream lifting costs, which is the valuation of the crude oil reserves (by subtracting the extraction costs from

the present net value). NNPC has also identified key challenges including asset integrity (pipeline leakage);

crude oil and production loss (from theft and vandalism); sub-commercial contracts (long-running legacy

contracts); and, the low capacity utilization of refineries.22 The second publication by NNPC retroactively

covered the period of January 2015-September 2015.23

NNPC is under fire with regard to approximately 21 million Euros in oil revenues that have failed to be remitted

to the state treasury. The Revenue Mobilization Allocation and Fiscal Commission asserts that NNPC has not

remitted as high as N4.9 trillion (EUR 21 billion) in oil revenue to the state treasury for the time period between

January 2011-December 2015.24 This information was revealed by the former Nigerian Central Bank governor,

Lamido Sanusi, which subsequently resulted in his dismissal by former President Goodluck Jonathan. NNPC

has rejected this figure and publicly stated that the number could not be more than N326.14 billion (1.4 billion

Euros).25

NNPC is known to have heavily engaged in wholesale corruption26 and a 6.8 million US dollar subsidy scam,27

among others. Corruption is rampant with regard to the awarding of licenses and blocks to the IOC in exchange

for bribes.28 Eni and Royal Dutch Shell, the subjects of an ongoing investigation, paid NNPC an amount of 1

billion US dollars for the rights to an offshore block (OPL 245). The funds were meant to be directed to the

state treasury, and instead it was bypassed and transferred into the accounts of a privately-held company called

Malabu Oil and Gas (owned by a former Nigerian oil minister).29 This case is currently under investigation in

the UK, Italy and Nigeria. Most recently, the Italian Police raided the Royal Dutch Shell’s headquarters in The

Hague, Netherlands, on 17 February 2016.30 It is also important to note that a key player in Nigeria, Eni, has

also been implicated in the Unaoil scandal in connection with bribery and corruption.31

Militant attacks also pose a problem in the distribution of oil production,32 and hundreds of thousands of barrels

per day (around 5 billion US dollars annually)33 are also being unlawfully rerouted because of oil theft on an

industrial scale; affecting every level of the supply chain and robbing the country of much needed oil

revenues.34

Angola fluctuates between being the first and second largest producer of oil in Africa.35 Given that 80 per cent

of Angola’s oil production is offshore,36 the government heavily relies on production revenues to support the

economy. Oil production and supporting activities makes up 95 per cent of the country’s exports and

approximately forty-five per cent of its GDP.37 The Angolan deepwater sector remains remain significantly

untapped, and its oil revenues from upstream E&P could compound exponentially in the event pre-salt E&P

(ultra-deepwater) proves to be successful.38 As of 14 April 2014, Sonangol has discovered more oil and natural

gas in the basin of Kwanza and Congo Rivers which might total up to 2.2 billion barrels of oil in reserve.39

Deep-Offshore” in Angola means any water depth beyond 150 meters.40

The oil crash has a devastating impact on the Angolan economy. Despite staggering oil revenues over the last

decade, the Angolan government has failed to diversify its economy and overwhelmingly relies on oil revenues

to fund its annual budget.41 In March 2016, Angola had no choice but to cut its spending by 20 per cent so that

the country can try and manage the effect of low oil prices.42 The revenue therefore derived through the

Angolan NOC, Sociedade Nacional de Combustiveis de Angola (“Sonangol”), is critical to the economy. The

B/E price for major offshore projects such as Total’s Kamobo (Block 32) is 80 US dollars per barrel43 which

greatly exceeds the current market price by 100 per cent. This differential results in a significant loss of

revenue. Angola’s leadership has further responded by deferring infrastructure projects, cutting expenditures

and even substantially reducing the salaries of government officials.44 However, if oil market does not rebound,

such efforts will mostly likely fall short.45

Nepotism openly rules Angola, and the Angolan elite profit from the oil revenues belonging to the Angolan

people. Isabel dos Santo (daughter of President dos Santos) is the richest women in Africa. In 2015, Isabel was

not only appointed to restructure Sonangol but also to the post of Commissioner for the Restructuring of the

Oil Sector and to the Urban Redevelopment Master Plan (Luanda).46 In these roles, Isabel dos Santos now has

15 billion US dollars of Angola’s future under management. The Boston Consulting Group and Portuguese

law firm Vieira de Almeida and Associates are also reported to be involved in the restructuring of Sonangol.47

The exact nature of the reconstruction remains to be seen, and thus far there have been no indications that this

restructuring will revamp Angola’s petroleum legislation. There are suspicions that the restructuring of

Sonangol might just be another smokescreen to divert funds derived from oil revenues into the private bank

accounts of Angola’s elite.48 These developments are occurring in the context of President dos Santos leaving

“active politics” in 2018, and the political backdrop of the expected upcoming elections in 2017.49

Other ongoing investigations include (and are not limited to) Sinopec. The current director of Sinopec,

Francisco Goncalves,50 is said to be key person that runs the Angolan oil fields. His name has been raised in

conjunction with the Unaoil corruption scandal, whereby Sulzer Pumps had promised to pay 2.5 per cent of

their equipment contract worth 20 million pounds into the Angolan Social Fund. Payments into the Angolan

Social Fund raise a red flag as PSC terms also mandate a payment into “social contribution” funds. There

seems to be little to no oversight over these mass payments made by IOCs,51 opening the door to social funds

being a conduit for bribes of public officials and more.

The Federal Ministry of Petroleum Resources has overall regulatory oversight over the Nigerian oil and gas

industry. The Ministry acts primarily through the Department of Petroleum Resources. Other regulatory bodies

include the Petroleum Products Pricing Regulatory Agency (to be repealed according to the Petroleum

Industrial Bill (“PIB”)), which regulates the rates for the transportation and distribution of petroleum

products.52

The PIB has also been around for the better part of a decade and is seen as being critical for further investment

in the exploration and development of offshore/deep water areas.53 The political will to pass the PIB has been

stymied due to political considerations, and most recently, the 2015 Presidential elections. The IOCs are also

publicly adverse to the adoption of the PIB, as the adoption and implementation of the PIB would lessen their

power from that of the existing protocol. The PIB aims to establish the NNPC as a public limited company,

rather than a government entity.

To further the process and give the PIB a chance of survival, in late 2015, the Nigerian government divided

the contents of the PIB into two segments: the Petroleum Industry and Governance Bill (“PIGB”)54 and another

segment that will address the fiscal and tax regime. It is the fiscal and tax regime that might have an impact on

the Nigerian deep water pricing process in the future. Analysts have stated that they would be surprised if the

PIB, or its new segments, would be passed within the next two years.55

The Petroleum Industrial Bill is said to overhaul the entire regulatory system related to petroleum. The 223

page document was drafted 12 years ago and as mentioned supra, has yet to be adopted.56 Key provisions in

the PIB which might affect the pricing of deep water E&P are Articles 226 (price monitoring) and Article 252

(gas pricing). As per the PIGB, the NNPC is expected to be replaced by the National Oil Company and the

Nigerian Petroleum Asset Management Company.57 In particular it is reported that

“The National oil company will operate as a commercial entity to be partly privatized (at least 30%). It will pay dividends from its operations to the federation account in addition to royalty and taxes.” The Nigerian Petroleum Asset Management Company will own and manage petroleum assets on behalf of the government. It will be responsible for the management of the oil and gas assets that do not require cash calls (upfront funding). The Minister of State for Petroleum recently estimated that Nigeria loses about US$15 billion annually as a result of failure to pass PIB into law. Other concerns in the oil industry which the proposed law seeks to address are lack of transparency, poor accountability, unclear roles of institutions, and weak regulations .”58

Section 5 of the Deep Offshore Drilling Decree addresses the terms of the Production Sharing Contracts (“PSCs”) between the IOCs and the NOCs (see infra) which are essential to the defining the pricing of oil between them.

Key legislation regulating the oil and gas sectors is the Petroleum Activities Law59 (Law No. 13/04, of 24

December 2004) and the Petroleum Tax Law (Law No. 10/04, of 12 November 2004). The Petroleum

Activities Law grants Sonangol an exclusive concession for the exercise of the mining rights for prospecting,

exploration, development and production of liquid and gaseous hydrocarbons.

Article 16 of the Angolan Constitution states that the solid, liquid and gaseous natural resources shall be the

property of the state, which shall determine the conditions for concessions, survey and exploitation of the

natural resources.60

There have been no indications yet that the restructuring of Sonangol will result in an overhaul of Angola’s

petroleum legislation.

When the issue of pricing was raised with legal and financial experts, they all indicated that PCSs were the

key terms of agreement between the OICs and the host country – it is rather the market and oil futures that

influence the actual price of crude oil. PSCs have become the preferred contract between IOCs and NOCs

engaged in deep water E&P in Nigeria and Angola, and give IOCs the right to explore for and produce oil

within the contract area or “block” for a specified period.61

The terms of PSCs differ from country to country, project to project, license to license and even block to block.

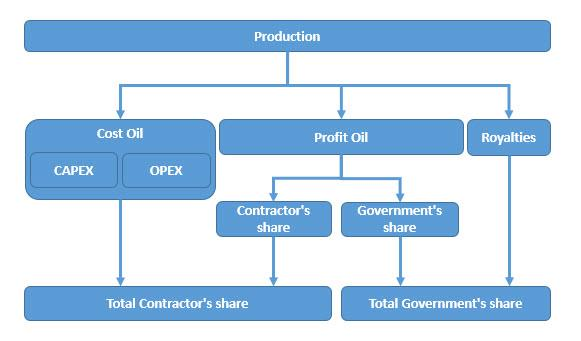

General terms in these PSCs that related to pricing include cost oil, profit oil, market price, royalties, incentives

and bonuses:

Nigeria lacks the knowledge, infrastructure and knowledge to engage in deep water E&P on its own. It therefore depends on IOCs to engage in this activity to obtain oil rents. PSCs were introduced in Nigeria in 1993 which in-turn fostered new foreign investment in this area.70 Nigerian PSCs generally cover terms related to bonuses, profit oil, cost recovery oil, tax oil and royalties.

| Area | Depth |

|---|---|

| (a) In areas from 201 to 500 meters water depth | 12% |

| (b) From 501 to 800 meters water depth | 8% |

| (c) From 801 to 1000 meters water depth | 4% |

| (d) In areas in excess of 1000 meters depth | 0% |

PSCs are the most common form of agreement in Angola. Under Angolan PSCs, the IOC bears all costs for the deep water E&P and related risks and losses.85

Risk Service Agreements (“RSAs”) fall under a special tax regime in Angola. This regime recognizes the IOC more as a subcontractor of Sonangol than a partner which is different from the PSC.102 In addition, a RSA levies the Petroleum Transaction Tax and Petroleum Production Tax which are not applied in the case of PSCs.103 Further “ring fencing” is expanded to include the concession area rather than just the development area, and there are different calculations for cost oil and the RoR.104

The price of crude oil derived from offshore/deep water production is driven by the market price of oil and oil

futures. As demand in the market for crude oil increases (or supply decreases), this will most likely result in

an increase in oil price. Conversely, if the demand in the market for crude oil decreases (or supply increases),

this will most likely result in a decrease in oil price. However, there is another layer to how the market impacts

crude petroleum prices – the oil futures market. The oils future market consists of future contracts that promise

to purchase oil at a set price on a specific date in the future. The commodities derivatives market and the influx

and outflow of funds, drives the oil prices up and down accordingly. This is thought to destabilize rational

speculation on the futures market. A NOC, for example, could hedge against risk and sell oil futures to lock in

a particular price per barrel of oil, especially if the view is that crude oil will trade lower in the future. Even if

the NOC were to do this, which is quite uncommon, such a strategy would only be beneficial for a limited time

period. With the high level of trading on the oil market, the NOC would not find anyone to purchase oil set

higher than the market price.

IOCs and NOCs set the prices for their crude oil production according to certain benchmarks. For example,

Niger and Angola set their oil prices according to Brent Crude benchmarks. Brent Crude serves as a benchmark

for two-thirds of the world internationally traded crude oil supplies.105 Other event-driven factors such as

natural disasters, world events, mergers and bankruptcy, etc. may affect the pricing of crude oil.

There are a number of way to manipulate the pricing and/or those PSC terms related to pricing to the benefit of the IOC. These include (and are not limited to) concerted actions among IOCs to manipulate oil benchmarks by providing “false inaccurate or misleading information”; gaming bonuses in PSCs; gaming the cost oil system to cross-subsidize; and, artificially increasing production costs.

Major oil producers in Nigeria use the Brent Crude as a benchmark for pricing their crude oil production.106 In

2013, Statoil, BP and Shell were charged with manipulating Brent Crude oil/future prices through price

reporting agencies (“PRAs”). Reporting information to PRAs is voluntary and not subject to any regulatory

oversight. All oil trading contracts are private and for the time being there is no way to ensure accurate

reporting.

In this case, the charged perpetrators allegedly reported “false, inaccurate or misleading information” to the

PRA. This misinformation impacted global oil benchmarks and affected the price of a number of consumer

items.107 Not only was an investigation launched by the European Commission, a NY class action claim was

also filed against Statoil, Morgan Stanley, Trafigura, Vitol and others. It is key to note here that Trafigura has

strong ties to Sonangol as well as key present and former politicians that have been known to obtain beneficial

ownership in companies linked to petroleum, energy and mining, among others.

Payments provided to NOCs in the form of bonuses are easily manipulated. As in the case of Sonangol, a portion of the signature bonuses might be earmarked for contribution to social funds. The IOC pays these monies as part of its contractual terms in the PSC, yet there are no safeguards or regulatory oversight as to where the funds land. In the recent inquiry into the Norwegian NOC, Statoil, and its relationship to Sonangol, a portion of the signature bonus had to be attributed to the financing of a research center project. Statoil came under fire because it reportedly had not taken appropriate steps to ensure that Sonangol established the research center, and the research center in fact was never been built.108 The amount in question is NOK 420 million (450 million EUR).109 This arrangement is by no means uncommon and serves as way to funnel hidden funds into the pockets of Angola’s elite.

If a PSC limits an IOC’s cost oil, it leaves room for the IOC to try to counteract this measure by “gaming” the cost oil system.110 If an IOC has a licensed blocks, one method to circumvent cost oil restrictions is through cross-subsidization.111 PSCs in Nigeria and Angola include provisions on “ring-fencing” to limit the cost oil to those costs associated with a particular block or license.112 IOCs can also artificially inflate production costs by drafting a budget that reflects higher costs than estimated.113 The IOCs will then obtain their exploration, development and production costs from the share of production or gross revenues which would be grossly overinflated.114

The swap deals and terms of the OPAs, such as those Nigeria entered into, can be opaque if for example, the contract terms are not published, and there is no public tender process.115 A country will resort to swap deals when it is in a bind and must maneuverer itself out, which leads to tough negotiations with traders and results in terms that are not ideal for the country-at-large, including large revenue loss.116 Additionally, the parties contracting with the host country can provide lower quality fuel and kerosene in return for the crude oil they are receiving as well as inflate prices and associated costs, thus negating fair pricing to increase their profit margin.